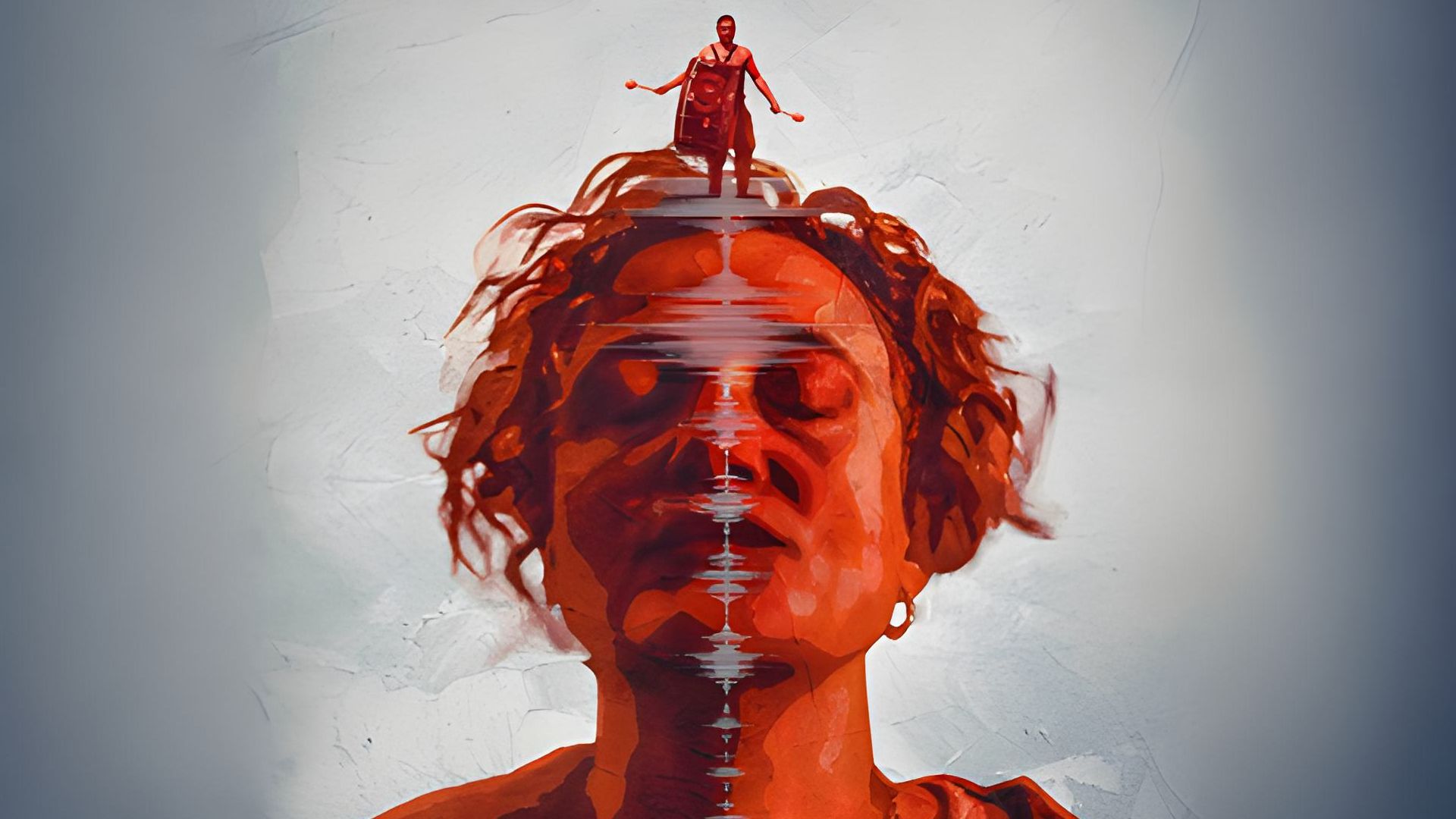

Black. It is the color that absorbs all colors, the shade that holds the sun’s warmth as it moves east to west. It is the color of a people, not just African but Caribbean, Middle Eastern, American, and more. But it is also music: the color at the center of the trumpet’s brass ring, the shadow that fills the club when the lights get low and the party begins. Over the decades, Latin music has built a reputation for being wildly popular, no doubt in part due to its danceable nature. But what often gets lost in the conversation is the contribution that Black Latines had in cultivating the sound that, today, many of us regard as uniquely “Latin.”

As a kid, I was guilty of just that. It wasn’t until years later that I came to understand the importance of claiming my Afro-Puerto Rican heritage and how it shaped not only my identity but also the rhythms that moved me. Yes, that’s rhythms, plural. From salsa to cumbia to reggaetón, an undeniable Africanía drives these genres. And it’s just as much a part of our music’s DNA as the language we sing it in.

The Rise of Machito, Afro-Cuban Jazz, and La Clave

We can’t talk about the influence of Black Latines and not mention Machito. Frank “Machito” Grillo, along with band director Mario Bauzá, pioneered the sound of Afro-Cuban jazz in New York City in the 1940s. They took the Big Band format that was popular at that time and added conga, bongos, and timbales.

These instruments are staples of traditional African music and provide Latin jazz with signature percussive elements and rhythmic structure. These elements would later become the foundation of salsa music, which evolved from son montuno and Latin jazz; it upped the tempo but kept the African fundamentals, especially “la clave.”

Growing up, my mother used to tell me that la clave was the heartbeat of salsa and, therefore, it was our heartbeat as well. However, while I thought of the clave as something uniquely Latino, the origins of the iconic “ta, ta, ta . . . ta, ta” began in Africa; la clave is an essential part of traditional African music. And even as the first slaves were ripped from their homes and crossed the Caribbean Sea with nothing but a lifetime of servitude awaiting them, la clave came with them. It was as simple as taking two sticks and knocking them together in rhythm, and it would become a staple of the music they produced. It would also eventually embed itself in Latin Caribbean music — not just salsa and son montuno, but other genres as well like danza, rumba, and mambo.

Similarly to jazz in the US, these musical genres would become an avenue to success for Black Latines worldwide and give rise to artists that would forever change the game, like Cheo Feliciano, Celia Cruz, Roberto Roena, Mongo Santamaría, and “El Sonero Mayor” Ismael Rivera.

The African Origins of Merengue, Cumbia, y Más

But it’s not just salsa and its predecessors that are heavily influenced by our African ancestry. Merengue, as we know it today, has its roots in the leisure time given to slaves, during which they would imitate the balls and ballroom dances of their European masters, creating something entirely new in the process. This music would remain mostly confined to the Dominican Republic until the 1930s when pioneer Eduardo Brito brought the music to New York. During the 1960s, merengue would experience another surge in popularity as Dominicans migrated en masse to the city, and Afro-Latino merengueros like Joseíto Mateo would help bring the art form to new heights.

Cumbia music, like merengue, has its origins in dances practiced by the slaves brought to Colombia. Over the years, it evolved to incorporate traditional European instruments and became popular across Latin America. While the sound became extremely popular during the ’90s thanks to pop artists like the late Selena Quintanilla and others, it’s important to remember that the first person to record a cumbia song was the Afro-Colombian artist Luis Carlos Meyer.

Yet another example of this fusion of African and European is the Mexican folk genre of son jarocho. It’s a staple of the Caribbean town of Veracruz, and I first heard of it when I interviewed singer-songwriter Silvana Estrada. When asked about her unique style and influences, the Veracruzan songstress spoke at length about the town’s African history and how it led to the creation of son jarocho’s unique sound.

Before Reggaeton, It Was “La Música Negra”

Before it was known by its current name, reggaetón went through a series of names and transformations. Reggae en español, melaza, underground, rap y reggae —the list goes on. But maybe the most fitting name for it was “La Música Negra.” Not only did this name epitomize the status of the underground movement that was burgeoning in the barrios, but it also identified it as a product of the Black Latines and Afro-descendientes that lived in them.

From El General and Nando Boom in Panama to DJ Negro and Tego Calderón in Puerto Rico, many of the genre’s pioneers in the ’90s and early 2000s were Black Latines. But beyond just the faces that flashed across the television during the music videos, the music itself was inherently African. Pulling from American hip-hop and Jamaican dancehall, reggaetón saw the European elements of Latin music scaled back in favor of an emphasis on heavy percussion. The dembow itself, though taken directly from riddims created by Jamaican producers, correlates with rhythms already found in traditional African music and Caribbean genres (such as Puerto Rican bomba).

The Issue of “Blanqueamiento” and the Invisibility of Black Latines

African influence has been a part of Latin culture since the very beginning, and that’s not even bringing Spain’s mixed African heritage into the mix. And yet today, if we look at all the genres mentioned above, we see that what started as Black music sung by Black artists has become progressively lighter. Reggaetón is a prime example of this, with artists like Karol G, J Balvin, and Bad Bunny all being lighter skinned. For this reason, remembering the African contribution to our music and our culture in its entirety is incredibly important. We must pay homage to the pioneers of these genres and also make space for today’s Black Latine artists to grow alongside their lighter-skinned counterparts.

Because at the end of the day, from the lightest to the darkest of us, our African heritage is something that we share; it connects us. And as we see when we take a closer look at our music, Latin music IS Black music. It’s high time we recognize it as such.

You can view the original article HERE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/02/27/879/n/1922283/f59299c265de40d6d77810.23288422_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/07/23/614/n/1922283/ca81e41a669fb3e9b06d96.09566328_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/27/355/n/1922564/200a549867e4fedbb431f6.99392381_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/26/639/n/1922564/e1f92baa67e40d467510a8.81927121_.png)