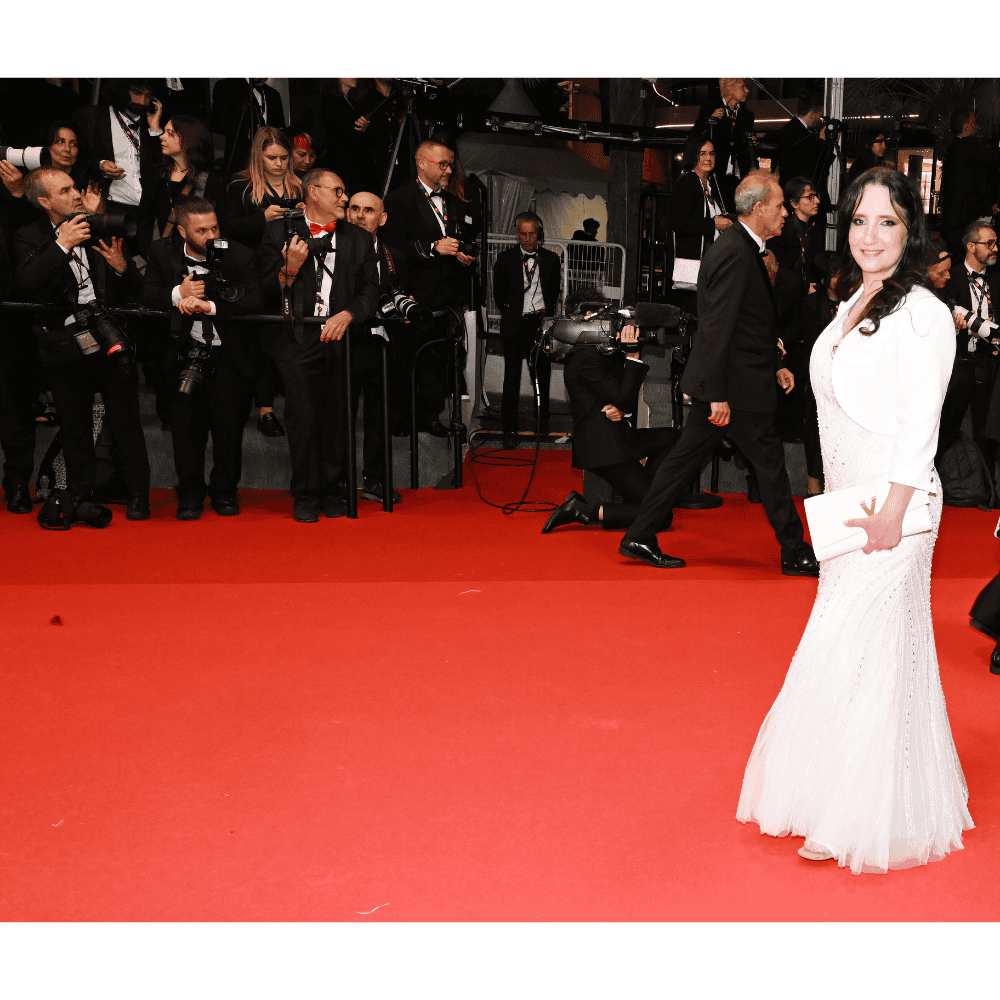

If you are not familiar with James Benning, you may regard the 80-year-old American filmmaker’s latest experimental and structuralist piece as nothing more than a surface level showcase into the modern phenomenon known as liminal space. Most of the exterior shots featured throughout Allensworth provide a simplistic, stretched out rural landscape with an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere that is coddled within. In all reality though, a much harsher but memorable message lies in wait for those who decide to go on this visual journey.

Creating 25 feature length films within a 40-year career thus far that include similarly made pictures like The United States of America and Maggie’s Farm, Benning once again wields a magnificent power through the cinematic style of a still shot in his newest release. Mysterious and slow yet unnerving and maddening all at the same time, he puts together 12 sections (that are five minutes each and coincide with each month of the year) which all focus on the archaic but preserved exterior structures that still stand in what was the first self-sufficient African American town in the state of California.

In one of the darkest periods of the United States where lynchings, segregation, and Jim Crow laws were omnipresent, a community was formed in 1908 by Allen Allensworth that became a beacon of unity. The 20 acres became a colony that was exclusively birthed by the hard work of African Americans, but was always destined to be plagued and troubled by the encircling footsteps of racism, ultimately making it a ghost town. All of these feelings and urges (whether inspiring or disturbing) are brought forth by the patient, brilliant cinematography within this film.

Death of a Subdued Society

James Benning

The unrelenting determination to make a comfortable life for themselves and a blatant opposition that was consistently fostered by a deep-rooted racism all still linger in that same isolated, ghostly space. Allensworth was founded along the Santa Fe rail line; six years later, though, the rail stop was forcibly moved to Alpaugh. Even so, Benning shows that all you have to do in order to be transported back in time is to stand still and let the camera do the rest. Before viewers even have time to innocently question the stylistic choice, the silent collision between America’s past, present, and future adamantly takes hold. Related: The League Review: A Breathtaking Retrospective of Baseball and Racism in America

Seeing a train that roars through one side of the background to the other or witnessing the tiniest of vehicles chug through the outer perimeter of this all but abandoned municipality shows that history always and unforgivably moves on from what once was. Clearly, these modes of travel are everyday occurrences, but Benning’s camera sees something we wouldn’t. When they are juxtaposed with the stillness and apparent death of a dream at Allensworth, these mechanical pseudo-lifeforms are highly noticeable and even antagonistic.

Poetry in the Name of Allensworth

James Benning

While the overwhelming remains of Allensworth are the explicit stars of this show, viewers (and Benning for that matter) also cannot ignore all the sounds of nature that mix into the framework of this faded utopia. Dogs, crows, chickens, and other assorted animals are all heard and assumed to be around, but since they are off-screen, this animalistic audio library that hauntingly flows from the scene does a complete 180 in purpose. Rather than breathing some much-needed conformability into this now derelict society, these grunts and carnal calls only complement the already negligent depiction shown on the screen.

As Benning coincides each exterior depiction with sequential months of the year, he also, at times, adds to these demanding sequences by slowly fading in a musical piece from great Black artists, such as Nina Simone’s “Blackbird” (1963) or Leadbelly’s “In The Pines” (1944). While these equally rugged selections tell about Black struggles from the time and stand in their own right as iconic pieces of music, the over the top presentation that results from combining the lyrical messages from these songs with the natural but deafening ambiance of Allensworth flies much too close to what was being achieved otherwise. The confrontational curiosity emanating just from the old homesteads and public service buildings is more than enough to captivate audiences.

On the other hand, young Faith Johnson is very much mesmerizing with her nuanced readings of Lucille Clifton’s poems during the month of August. It’s successful alone in treading that burning line between atmospheric and straightforward narrative. Related: Best Movies Based on Poems, Ranked

Facing the Future Through the Past

James Benning

A great assumption could be made with Benning’s projects that the simplicity therein is deceiving. As with Allensworth, time could be spent analyzing that one single open blind among the many that are closed for some untold storytelling cues, or perhaps plot paths could be paved from any possible shadows that lay deep within the decaying stable. New aluminum siding that is mixed with the original architecture teases a reemerging spirit. Flags and trees wave in the wind as the buildings remain stoic, unchanged by all the troubles they’ve seen but just waiting to tell their story.

There is not a question that these forgotten architectural figments are all soul-stirringly allegorical and symbolic in different ways, but there is also a beauty in just the plain painful journey. Through these naturally stimulating still shots, Benning wholeheartedly (and quite easily) deconstructs America’s sinful past and puts it right in front of the audience’s face. He magnifies not only the barren space and utilizes the quietness to its fullest potential, but also crafts a reminiscent look into the tense and trying times of what would unknowingly be a lost future for Mr. Allensworth and his faithful followers.

The movie does certainly require concentration; it is undoubtedly an experimental film, but a relatively brief one. Up until the screen goes black for the final time, this one piece of landscape cinema takes you on a heavy journey through the desolate homes, schools, stores, and churches that you won’t be able to forget anytime soon.

James Benning’s Allensworth will screen at the New York Film Festival.on Oct. 8 and 9. You can find more information at the NYFF website.

You can view the original article HERE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2022/01/31/928/n/1922564/d3ab283161f851c4033582.14757686_.jpg)