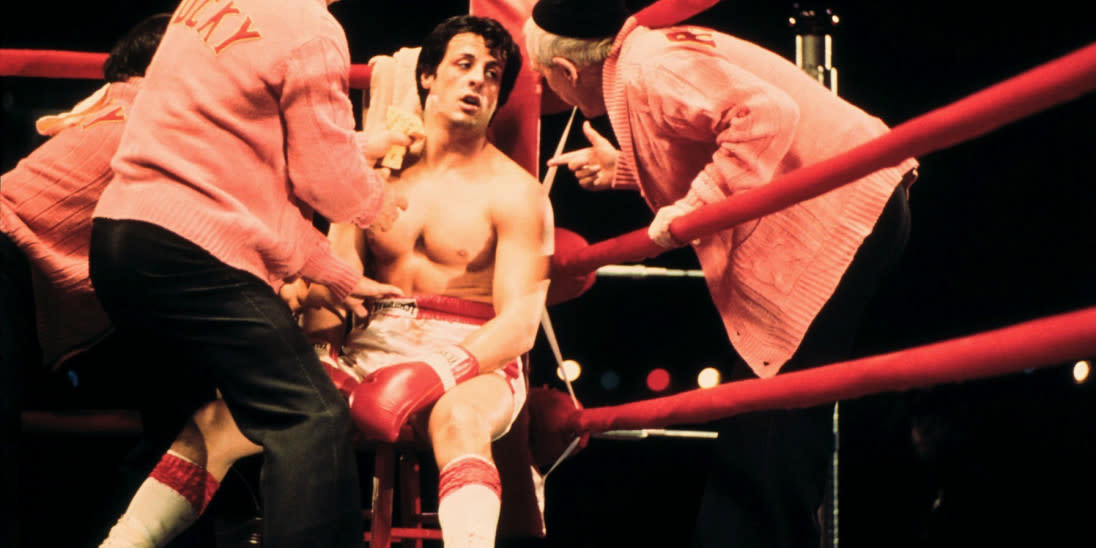

Sylvester Stallone is synonymous with the character of Rocky Balboa, the scrappy underdog boxer who first brought him to the spotlight in the ’70s. But in recent years, Stallone has made it very clear that even though the films are inextricably linked with him, he’s not happy about the way the original deal was structured and thinks he should have received an ownership stake.

On July 31, following the announcement of a “Rocky” spinoff film in development about the characters of Ivan Drago (Dolph Lundgren) and Viktor Drago (Viktor Drago), Stallone took to Instagram to express his frustrations about the direction of the expanding franchise, and particularly its longtime producer Irwin Winkler. In a since-deleted post, the actor called the 91-year-old producer and his children Charles and David Winkler “vultures” and “parasites” who he says are exploiting the franchise. Earlier in July, the actor posted another (also now deleted) Instagram of portrait of the producer as a serpent, voicing frustration that he had allegedly been deprived an equity stake in the “Rocky” franchise.

More from Variety

Although Stallone’s invective against Winkler has heated up in the past month, it’s been bubbling for several years. In 2019, a year after the actor reprised his role as Rocky for the second spinoff “Creed II,” he sat down for an interview with Variety‘s former editor-in-chief Claudia Eller in 2019 to disclose his frustrations regarding the ownership situation of the franchise. Stallone — who wrote the screenplay for the film in three days, before selling the rights to producers Winkler and Robert Chartoff — said his anger came from the fact that the original deal deprived him of an equity stake in the franchise, a longterm asset that could be passed to his children after his death.

Story continues

“I was very angry. I was furious,” Stallone told Variety about the terms of the original “Rocky” contract. “‘Rocky’ is on TV around the world more than any other Oscar-winning film other than ‘Godfather.’ You have six of them, and now you have ‘Creed’ and ‘Creed II.’ I love the system — don’t get me wrong. My kids and their kids, they’re taken care of because of the system. But there are dark little segues and people that have put it to ya. They say the definition of Hollywood is someone who stabs you in the chest. They don’t even hide it.”

Representatives of Stallone and Winkler did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Jason E. Squire, professor of cinematic practice at University of Southern California, called the situation of a major star directly and publicly calling out a prominent producer “very, very rare.” In terms of how Stallone and other stars get paid for their work on projects, Squire explains that stars usually get paid via cash upfront as well as back-end residuals dependent on the success of the film. In Stallone’s case, although he does not have ownership rights over the film, he continues to make money from the project via back-end payments.

“Big stars are paid in two ways: cash up front, which is part of the budget, payable in weekly installments during shooting,” Squire said. “And then there’s the back end known as contingent compensation, which could be in the form of some kind of formula based on the success of the movie, the theory being sharing in the success.”

While Stallone’s public dissatisfaction with the ownership situation hasn’t spilled over into any legal action, disputes over copyright and ownership over fictional characters are fairly common, and almost always go in the direction of the content owner. The comic book realm is particularly rife with with legal battles from the estates of creators like Jack Kirby over the characters they created — such as the Fantastic Four and X-Men — ending in courts ruling in Marvel or DC’s favor.

James Sammataro, partner at Pryor Cashman and co-chair of the firm’s media and entertainment group, explains that these cases rest on a provision in copyright acts that Congress developed for cases before the current 1976 copyright act, due to an inequity of bargaining power in deals made before that time. In this provision, after a roughly 35-year period after the original deal, creators can issue “termination rights” to attempt to reclaim their copyright.

The reason why many of these cases go in favor of the current rights holder, according to Sammataro, is because it rests on proving that the original work was developed outside of a “work for hire” situation, or that the project was developed without being commissioned by the rights holder for the express purpose of selling the work. With comic book properties especially, the cases have found that the works were made for hire, and as such the courts have sided with the rights holder.

“When you do something as a work made for hire, your company that you’re rendering the services to becomes the owner,” Sammataro explains. “In most of those instances, the facts have lined up that it was a work made for hire, such that the employer or that company provided the tools, heavily edited the project, farmed out the work, essentially was the governing spirit behind the work and the person was more of a scribe as opposed to the creative source for it.”

For a case that ended in success for the original writer, Sammataro pointed to a 2018 lawsuit regarding “Friday the 13th,” where original screenwriter Victor Miller received full ownership over the original screenplay after the court ruled in his favor, as an example of the termination rights succeeding. In that case, the court ruled in Miller’s favor by stating that the original screenplay was not made on a work for hire basis, not prepared within scope of employment, and that he was an independent contractor working on the project.

Jody Simon, a lawyer for Fox Rothschild, who specializes in representing comic book creators and independent studios, says in the “Rocky” situation, the original script probably wouldn’t be considered work for hire due to the backstory of Stallone writing the script himself before shopping it to studios. However, he emphasized that doesn’t necessarily mean that Stallone has a case. Once he sold the script, it went under the ownership of Winkler, and whether or not he had an ownership claim depends on the specifics of the original deal.

In the case of the “Drago” spinoff, where the character was introduced in the sequel “Rocky IV,” Stallone’s claim over the character is even hazier. As the character was introduced in a sequel after “Rocky” became an established property, the chances of the court ruling it was a work for hire situation is probably far greater.

“From reading the articles, I don’t think Stallone was threatening to sue, I think he’s just complaining and trying to guilt Winkler into changing the economics,” Simon said. “I infer from the tone of what I’ve read in the press that he doesn’t have an ownership claim. If he had one, he probably would have asserted that.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Click here to read the full article.

You can view the original article HERE.