“Ozark” is a show about balance. Initially the scales had only two weights to consider: Marty Byrde’s (Jason Bateman) bookkeeping finesse and emotional stability versus the Navarro drug cartel’s 50/50 choice of killing Marty or allowing him to launder their money through various businesses in the Ozarks.

As time went on, a bevy of other figures joined the scales, vying for ultimate heft: Wendy (Laura Linney), Marty’s wife, and her consummate disdain for and desire to bend her new life to her will; Ruth Langmore (Julia Garner), an Ozarks native whose intelligence and courage are constantly undercut by her socioeconomic background; Jonah Byrde (Skylar Gaertner), Marty and Wendy’s son, who learned to launder from his dad but has very different ethical principles than his parents. “Ozark” isn’t as flashy a production as “Breaking Bad” or “Mad Men,” or even older series like “The Sopranos” or “The Wire,” but has proven itself just as capable of the writing, direction, and acting on other, more high profile prestige dramas. These last seven episodes of Season Four do not disappoint.

Navigating the delicate nature of power dynamics is integral to Marty’s characterization, and therefore to the writing of the series. The Navarro cartel and their associates conduct crimes, occasionally doling out extreme violence, so Marty must course-correct. Jason Bateman’s performance as a quiet, mild-mannered financial adviser is a study in emotional anchoring. If Marty Byrde seems boring or dull to the audience, it’s because he’s the one holding this entire house of cards together. His body moves casually, but with purpose. Half the time when he’s en route to committing a host of felonies, you’d think he was just heading out to buy eggs or put gas in the car. Bateman’s careful, calming presence takes the audience back to the math: this is a story about the secrets a spreadsheet can hold. Marty is the black coffee-guzzling hangover cure to Wendy’s wild, greedy villainy. This holds true all the way through the finale, and his character’s payoff is just, and, like the man himself, sensible.

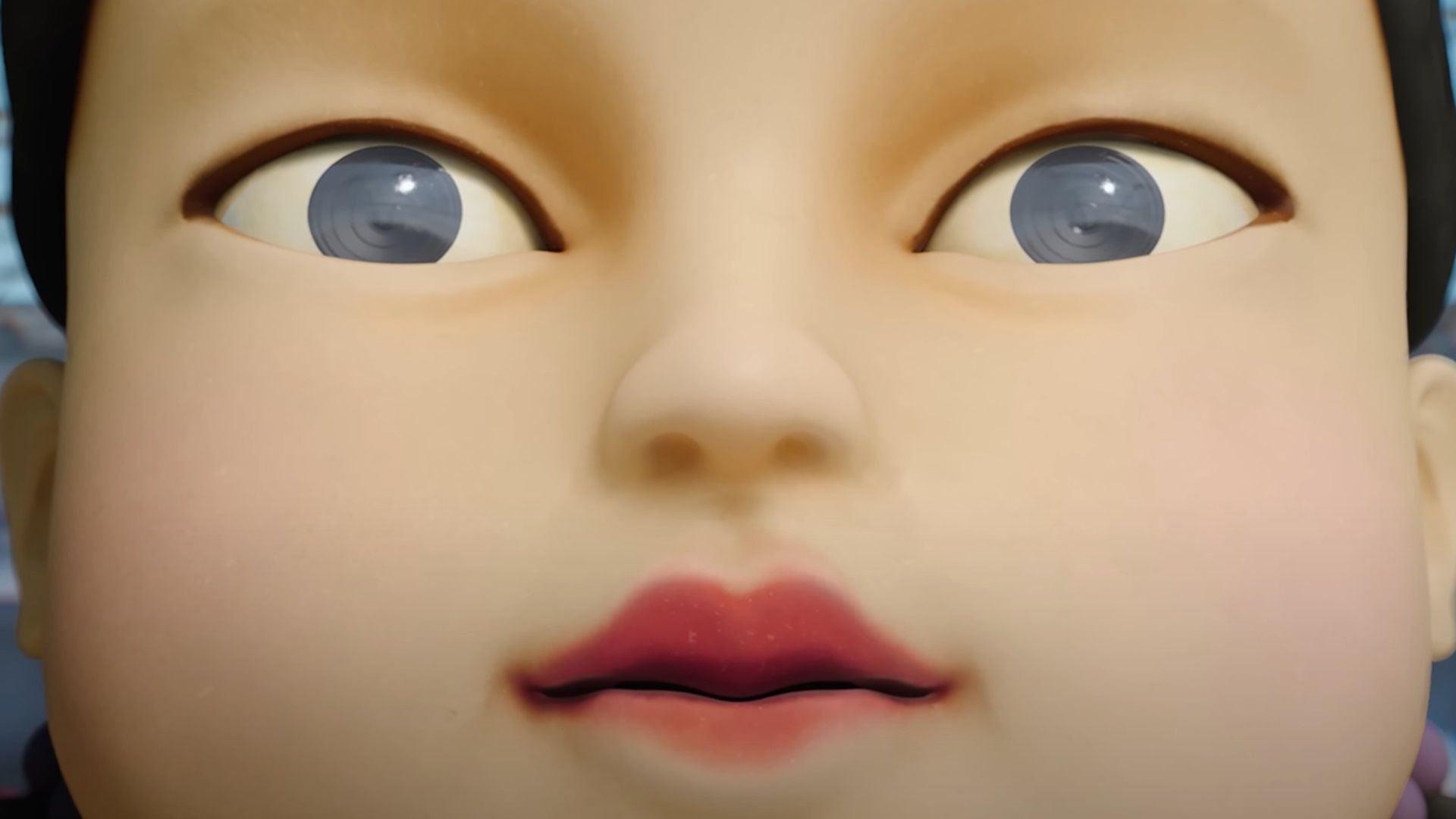

If Marty is the yin, then Wendy is the yang. In my review of Season Four’s first seven episodes I said Laura Linney was firing on all cylinders. Somehow, she intensifies her performance in the back half of the final season. A serene, soft, yet unemotional glint lights up her eyes when she’s insulted by a loved one. When she scoffs at others’ fears and anxieties, Wendy’s dismissals land like anvils. Linney delivers Judgment Day-style censures so severe a firing squad would be kinder. By now the audience knows that Wendy Byrde was born and raised in an environment not unlike the Ozarks. Immediately the repulsion caused by the Ozarks gives Wendy demented inspiration. Once upon a time this culture, these values suppressed her, shamed and bullied her. But she’s not Wendy Marie Davis anymore. She’s Wendy Byrde of the Byrde Foundation, formerly laundering money for the Navarro cartel, now a completely legitimate enterprise. It’s not fair to call Linney’s performance a new standard bearer for villainy, because what she’s done in this part holds a Shakespearean richness, but it is inflected with something unidentifiable. Sometimes Wendy’s actions seem tinged by genuine sorrow over her brother’s death, or propelled by love for her children. Sometimes she seems to operate out of pure spite, or unmitigated greed. Most frightening of all—and this is why Linney’s Wendy is an acting hallmark—sometimes there’s nothing behind Wendy’s actions at all. She is an abyss, one that will cause lethal injury just by returning your gaze.

You can view the original article HERE.